Educational ‘Best Evidence Synthesis’

Removing education from situated politicians and their political agendas

I was going to start this by stating that no government presents a teaching and learning agenda to deliberately hinder a students progress. However, in the thirty years that I taught in the New Zealand education system, there are a number of party political initiatives that don't necessarily support this thesis. Right at the top of such a list is the hoary annual of standardised testing.

An illustrative example: back in the days of sixth form certificate in the 80's all science students had to sit a standardised test midway through year 11 and based upon these results each school was allocated levels of achievements that could be obtained for all students in that school the following year. Accordingly a year later, no matter what progress a child was able to make, their achievement potential was already set in academic concrete by results obtained in the previous academic year.

When making any judgement regarding the efficacy of standardised testing ST one first needs to understand what reasons there are for reinstating this method of assessment. In America ST was the cornerstone of Barack Obama’s educational directive of ‘no child left behind’. The late Sir Ken Robinson, an expert in the study of educational paradigms, in response to this initiative, stated that anyone who doubted Americans grasp of ‘irony’, the results of this project was conclusive evidence that they fully understood, since it had failed so miserably to deliver on such a promise.

Perhaps the biggest criticism of standardised testing when used a priori is that it offers only a crude snapshot in the achievements of a child on a given day and is not indicative in any way of a child’s actual attainment, making no recognition of the wider learning or understanding that a child may or may not have demonstrated in performance based assessments PBA prior to or after such testing.

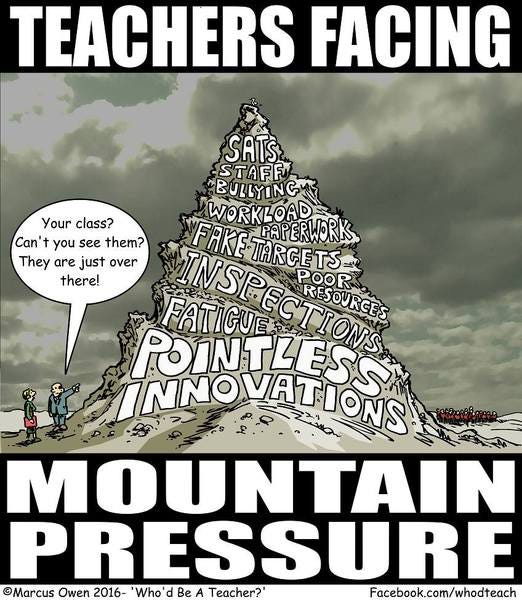

What ST is very good at is victimising a child for a whole raft of circumstances out of their control, beating teachers with a big stick for having ‘failed’ in their duties to educate children and condemning schools via a league table that ranks performance against others.

Many schools already utilise some form of standardised testing to identify students who need remedial care, but it is not used as a stick to either victimise a student, the teacher or a school, but rather as a means to prioritise and deliver targeted help to those most in need.

So by further examining reasons why Erica Stanford has reinstated ST perhaps the answers are to be found in rhetoric, dogma, and a determination to ignore empirical evidence. The overwhelming evidence concerning ST is that it is a failed yardstick by which to measure any relevant academic progress of any student at any level. As far as dogma is concerned it may be posited that Right-Wing solutions have had an historical tendency to postulate bland, simplistic and one dimensional answers to complex issues, under what other circumstances could we be faced with the introduction of ‘boot camps’ to meet violence upon those ‘delinquent’ anti-social elements of our society who have hitherto only experienced violence in their upbringing, or to answer the ‘problem’ of gang affiliation by the banning of patch paraphernalia? Now regarding rhetoric, perhaps it is here that the real agenda is discoverable. To rewrite the sexist meme thus: ‘behind every great woman is a great man’, can we not detect the spectre of Seymour and his obsession with the neoliberal education imperative of Charter schools lurking in the shadows of Stanford, waiting to pounce on underperforming ST state schools and hand them over to the profit takers?

The unpalatable truth is as long as education remains away from the hands of educationalist, students will be the losers in any real determination to provide best practice outcomes.

It has been reported that Ms Stanford is particularly concerned for the poor outcomes of Māori and Pacifika students in New Zealand. If this is so I applauded her focus. I will leave aside any argument that points to evidence of an inherently racist curriculum that alienates and/or disenfranchises these students from their learning potential and instead focus on another equally unpalatable truth that deserves much more resources and attention if raising student achievement is the true goal.

Educational ‘Best Evidence Synthesis’ first published in 2003 by Sarah Farquhar followed closely by others including: Adrienne Alton-Lee, then Fred, Jeanne and Chris Biddulph, also Linda Mitchell and Pam Cubey all offer comprehensive, compelling, and revealing evidence that ‘deficit thinking’ is one of, if not, the greatest barrier to student outcomes

The thesis posits that teacher expectations of children’s outcomes are a major driver of academic attainment, or of behavioural expectations in classroom interactions and that students from lower socio-economic backgrounds or from Māori or Pacifika ethnicities are particular targets, often unknowingly, of both experienced and inexperienced teaching staff. Since the early millennium the BES project has offered in-depth individual and school wide professional development to first identify and then to address ‘deficit thinking’ across teaching institutions. The results have been astonishing. The realisation of individuals and of schools to this issue and the methods to address such negative attitudes has been hugely instrumental in raising the performance and outcomes of students hitherto expected to ‘fail’

For the school and as a teacher within it this professional development was the most profoundly important work ever undertaken. There is a truism stating that life reflects what one believes. I know as a teacher whenever I entered a class looking for troubles I always found them. Thankfully I mostly only ever looked for the good and was NEVER disappointed. Similarly I always enthusiastically greeted latecomers. To watch their demeanour change in an instance to the welcome was pleasure enough. BES with the focus on strategies for overcoming ‘deficit thinking’ placed meat on the bones of a learning environment that I had always intrinsically believed possible. It became the empirical evidence upon which, not just the school I worked at but, countless others schools and teachers across the motu studied and built a pedagogy to improve the performance of all students.

No child needs to be branded a failure. ST rather than PBT rewards the child that has a superficial grasp of information, that responds easily and quickly under pressure, and that comes from mostly middle to high income socio-economic back grounds. PBT offers evidence of metacognition, deep learning and creative processes, where information is not merely stored in learning silos, but is accessed, understood, and reorganised by the student.

An erstwhile colleague of mine, John March now long deceased, took an exchange year to Kansas in the early 80’s. As a social studies teacher he encouraged debate regarding information and facts collected and presented , recognising that all arguments are situated. He spoke of how he got his students to rearrange the desks in his class in a circular manner to encourage a more inclusive, equal seating plan and how very early on in this ‘experiment’ he encountered resistance from a student body that was not used to this kind of learning. Common questions centred around whether the students were going to be credited for their participation in the debate, or whether information covered was going to be ‘in the test’. John met two reactions when his reply was in the negative. For a few ‘high achievers’ this was their signal to switch off. If it didn’t go towards their term grade it was irrelevant therefore not worth their attention, whilst for the vast majority of the rest of his class they welcomed enthusiastically the opportunity to be involved in a practice that was open-ended, had no ‘right or wrong’ that might embarrass or lower their social standing yet which challenged them to construct arguments that made sense with the information they were asked by John to research.

The refocus on Reading, writing and mathematics by the current administration is a complete red herring and a renewed effort to return to a learning pedagogy that infers ‘ if it’s not in the test, it’s irrelevant’. This move is not at all surprising, indeed the surprise would have been if the government really was interested in a relevant and meaningful education for life. The knee-jerk reintroduction to standardised testing is the corollary for such a narrow minded neoliberal view of education.

Not unrelated to Ms Stanford’s drive towards the ‘3 R’s, one of the final propositions I attempted to promote in my last years before retirement was that the eight learning areas of The Arts, Languages, Social Sciences, Science, Tecnology, Physical Education, Mathematics, and English all had equal allocation of time in the lower school of secondary education. Students at this level have limited choice of what they study so the idea that a hierarchy of disciplines exists in education seemed an irrelevant and imposed narrative if the ‘whole’ child’s potential was to be valued. The concept nearly won the consensus, but was defeated oddly enough by the HOD of a department most threatened under the hierarchical nature of the time table, and who would have gained more allocated curriculum time as a result, under the new order. That left an extra 3 hours curriculum time to be allocated and in the ensuing bunfight the status quo was reestablished and I resigned my place on the curriculum committee to resume banging my head on the brick wall of intransigence. For me the debate was of defining importance. The way we offer subjects to students and the hierarchy in which they are presented demonstrates two things, one certain subjects are important, and others not, and two, if you’re no good at the subjects we say are important then you are a failure! The importance we place on certain areas if the curriculum and how we choose to measure success in these consigns vast numbers of the participants into believing they are failures.

Many students, for the remainder of this governments term, are going to be forced to needlessly focus on subjects and a testing regime that exposes their ignominy of what they can’t do, in subjects they have little interest in at that stage in their lives or that have no relevance other that that they have been told are important. For lots, the very things they are good at or inspire and interest them, have been devalued, not offered or actively dissuaded as pursuits on the grounds they are not viable career options.

This government doesn’t seek to improve teaching outcomes in real terms. If it did why anoint a person with absolutely no educational expertise to oversee policy change? Educational improvement requires expenditure of far greater sums of money in all areas be it infrastructure, recruitment and retention of high quality teaching graduates, or the in-depth sustained and continuous professional development of all staff. A committed government would remove all non experts from arguing in ignorance about what is or isn’t ‘best practice’ and begin instead a comprehensive recruitment of educational experts from across the globe.

Excellent piece Mike. I'm going to sound like a dinosaur - I started primary/intermediate teaching in 1967and finished 35 years later after experiencing many different parts of the country, classes from New Entrants to Year 8 and up to Principal level. In all those years the teaching and learning that took place in classes where teachers understood child development, provided a wide learning experience in and out of the classroom and, most importantly perhaps, enjoyed teaching and children (not all did), provided a brilliant foundation for later learning and enjoyment of it. Of course, there were children who struggled and the level of support for those children was patchy or poor but in general they would come to school in that environment with a positive attitude. Standardised testing is as far from that approach as you can get and won't improve educational outcomes nor will it encourage innovative, creative and committed people to enter teaching.

A well written synthesis of the concerns many of us hold about the direction of the initiatives proposed at the moment. The brave administration would propose that education is no longer a political football and create legislation that forms a bipartisan approach if they want to create real and sustainable change... but alas, we have not have an administration brave enough to even bring it to a public debate.